I commenced this journey to realize who I was; to understand what I was and what pushed me forward. To do that, I felt I had to draw up my own self-image. I began to wonder if art creation as a phenomenon could not be seen as a kind of self-image in its own right. This idea fascinated me and I started working with it. As a transgender person – someone who does not fit into the normalization of society – I had been living in constant lack of harmony and in a struggle with my society and surroundings. I had always experienced me in a different gender than I was born in, always playing a role in order to fit; but who was playing? Was it me who was playing someone else? Was I this man that I projected? Was I the actor behind it? Or was I the person – the trans – that was hidden behind? I was born as a boy. Obviously, I figured, I was not my body. I felt much more me when I snuck out as a girl. The body said male but I identified as a woman! The body is something that represents me – it is not me. But representing what? Who?

I looked back at my own art creation over the years and realized that this being – this woman – was in some way always there. Present in my artwork now staring back at me clearer that a bright moonlight I saw her there! – years before I had consciously admitted to myself that I was trans. It was as if she was trying to let me know – contact me – through my art. But who was contacting whom?

To explain who I am – who is thinking, writing these words – by saying it is a result of a specific brain activities, restricting it to mere physical activity, is to me a bit like explaining a novel by describing the book. My body is a body of a man; I was born as a boy and I have a man’s genitals, appearance and upbringing. However, clearly, I am something other than what is seen on the surface – something more than my physical appearance reveals. I thought I could see glimpses of it in my art observed in a retrospect. This idea of my art revealing my true real self, became the pivot point in the SNART artistic philosophy. SNART is a for me a certain approach to art and art-making. It is a living-art Arte Vitae of sorts. I can see now that me coming out as a trans-gender person and acting a role of a trans-woman is certainly a performance a SNART – performance. This performance, this Arte Vitae performance lasted over a decade. I was totally involved, dedicated and absolutely absorbed in the performance. Only later, a year or two into my undergraduate study at the Icelandic University of the Arts, I began to realize it was an act – a performance. Since then I have build on this realization.

I found I could use this concept to read other people’s art. I could use it to read art in general and what’s more – I could use it to see society’s Self–image through contemporary art making. In a way, art making, the apparent conscious choices of subjects, mediums and context, is in a way like automatic writing. Looking at an artist’s work reveals his or her Self– image, regardless of what was consciously wanted or intended. I had discovered a key! A key that unlocked a hidden pathway that could reveal the reason for making art. Why individuals choose the path of art making and why they choose a certain genre in art – and it was all through the narrative that was present in art making when seen in retrospect .The narrative of the Self – the SNART!

Let me explain a little further.

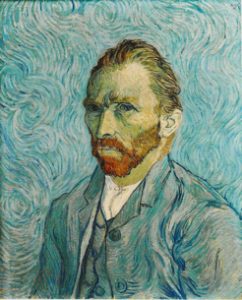

For most people it is no challenge to regard a self portrait like – say one of Van Gog’s, as a depiction of him. Most can read into his persona through these artworks, see him as a person and even sense what kind of person he was. Even explaining to a layman that there we have a subject object merge consist of no challenge. What I am about to argue, however, is that in almost every single piece of art making one can see the self image of an artist in a very similar way.

As case in point I’d like to take an example of the famous painting Las Meninas by Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660).

Much has been written about this magnificent painting. Interpretations are, perhaps, as many as those who have endeavored into the subject, but whatever else can be said about it, what is clear is that here we have a self portrait of the artist Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velazquez. On the outset, it might appear that the painting is depicting a portrait of princess Margaret Theresa of Spain and here entourage, but a short peak under the surface reveals this as a portrait of the court painter Velasquez. Not only can we see his glance in the background, but he is painting his studio, his conditions and life; the painting is telling the story of the artist – it is his Self-Narrative or SNART.

To use an example from the contemporary art world, I want to use an example that has no reference to the artist’s physical body in its work. Bill Viola (1951) is a video artist. He uses models in his works that characterizes in slow movements and water is prevalent in many of his works.

The above examples from Viola’s works have several things in common other than being all Viola’s work. For one, they all have water as a fundamental element in them. Viola’s work are dreamy and a main characteristic of his works are the slow movement the drives them on. Viola has described his works as being moving paintings. I do not want to make the impression as to it being necessary to know the artists story to enjoy his art and certainly there could be many ways to interpret and read his works, but I do want to reveal an important fact about Bill Viola to point out the SNART element in his works: When Viola was a child he was one day sailing on a boat on a lake with his uncle. An accident happened and the little boy fell overboard. This day Viola nearly drowned. Viola has described the incident as being in a slow motion surrounded by blue light and the sounds all being dim and heavy. This was a near death experience but the uncle managed to grab the kid and save his life. The reason I am conjuring this fact about Viola is not to add some extra into enjoying his works. My purpose is to show that this narrative – this Self–Narrative, is in one way or another prominent in so many of Viola’s works. Many of Viola’s works are on the hinge of the supernatural. There is a occult sense in them, something outer-worldly. The artist has expressed his views on spirituality and the profound change this incident had on him. This can all be seen in his art – this is his SNART.

To sharpen this idea, I want to point towards the works of Anselm Kiefer (1945). He was born into the ruins of the post war Germany. The environment was nothing short of apocalyptic. Kiefer has described how he and his friends used to play in the rubble of bombarded buildings and that he finds some beauty in destruction. He sees potential and rebirth in death and his art surely demonstrates resourcefulness and hardship – trades that were essential for the survival of his generation.

Looking at Kiefer’s works, we see this story. We see a macabre world. World full of harshness, numb like after a head blow. Rumble corridors and war junk that has taken on some transcendental aura.

Kiefer uses Sunflowers a lot in his works. He presents them when they have lost their vitality. The pedals are gone, but this is when they bear the fruit of the next year’s season, full of dried hardened seeds. This is Kiefer’s SNART. Seen in context we can clearly see his portrait in his works – a person born into horrible devastation, someone forced to make the best of it and someone able to see the regeneration of death and destruction.

To emphasize what I mean by Self, I want to conclude with an example of one abstract artist. Donald Judd (1928–1994) worked with minimalistic forms. What I want to demonstrate here is that we can also derive SNART, i.e. the self–narrative, from what is chosen not to be said or displayed in artworks as much as what is.

What appear might be a mechanical image, something fabricated out ISO standardized units, emanating from the industrial of the twentieth century. There is something immensely impersonal in Judd’s works. Mass production, harshness and standardization; there is a loneliness in globalization. The sense of belonging has gone. We see in Judd’s works a hardened individual. Someone with fierce dedication to succeed. There is a modern individual, organized and dictated by his calendar and clock. No feeling, no emotion emitted – no weakness. This is a portrait of a winner, an alpha; someone who finds comfort in the spotless surface of the mechanical, the exactness of mass production, the shelter of autism.

I have taken here some widely known examples from art history to demonstrate the essence and the idea behind SNART. SNART is a way to look at and analyze art. It is a philosophy in the way it demonstrates a system that allows for deepening our understanding of the Self and hence our existence.